DECLINE OF INDOLOGY IN THE WEST

Indology, which is the study of Indian history and culture from a Western perspective, is rapidly declining in the West under the impact of science and changed global conditions. Just as Max Müller represented Indology at its height, Michael Witzel symbolizes its current decadent state.

N.S. Rajaram

ABSTRACT

Indology may be defined as the study of Indian culture and history from a Western, particularly European perspective. The earliest Westerner to show an interest in India was the Greek historian Herodotus, followed by his successors like Megasthenes, Arrian, Strabo and others. This was followed by missionaries, traders and diplomats, often one and the same. With the beginning of European colonialism, Indology underwent a qualitative change, with what was primarily of trade and missionary interest to becoming a political and administrative tool. Some of the early Indologists like William Jones, H.T. Colebrook and others were employed by the East India Company, and later the British Government. Even academics like F. Max Müller were dependent on colonial governments and the support of missionaries. From the second half of the 19th century to the end of the Second World War, German nationalism played a major role in the shaping of Indological scholarship.

Much of the literature in Indology carries this politico-social baggage including colonial attitudes and stereotypes. The end of the Second World War saw also the end of European colonialism, beginning with India. Indology however was slow to change, and with minor modifications like seemingly dissociating itself from its racial legacy, the same theories and conclusions continued to be presented by Western Indologists. Towards the close of the twentieth century, first science and then globalization dealt serious blows to the discipline and its offshoots like Indo European Studies. This is reflected in the closure of established Indology programs in the West and the rise of new programs within and without academic centers driven mainly by science and primary literature.

The article will trace the origins, evolution and the devolution of Indology and the main contribution of the field and some of its key personalities.

Background: Historiography

One of the striking features of the first decade of the present century (and millennium) is the precipitous decline of Indology and the associated field of Indo-European Studies. Within the last three years, the Sanskrit Department at Cambridge University and the Berlin Institute of Indology, two of the oldest and most prestigious Indology centers in the West, have shut down. The reason cited is lack of interest. At Cambridge, not a single student had enrolled for its Sanskrit or Hindi course.

Other universities in Europe and America are facing similar problems. The Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium, long a leader in Oriental Studies, is drastically cutting down on its programs. Even the Sanskrit Department at Harvard, one of the oldest and most prestigious in America, shut down its summer program of teaching Sanskrit to foreign students. It may be a harbinger of things to come that Francis X. Clooney and Anne E. Monius, both theologians with the Harvard Divinity School, are teaching undergraduate and graduate courses in the Sanskrit Department. More seriously, they are also advising doctoral candidates.

Does this mean that the Harvard Sanskrit Department may eventually be absorbed into the Divinity School and lose its secular character? In striking contrast, the Classics Department which teaches Greek and Latin has no association with the Divinity School, despite the fact that Biblical studies can hardly exist without Greek and Latin. It serves to highlight the fact that Sanskrit is not and can never be as central to the Western Canon as Greek and Latin. It also means that Sanskrit Studies, or Indology, or whatever one may call it must seek an identity that is free of its colonial trappings. It was this colonial patronage in the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries that sustained these programs. Their slide into the fringes of academia is a reflection of the changed conditions following the end of colonialism.

Coming at a time when worldwide interest in India is the highest in memory, it points to structural problems in Indology and related fields like Indo-European Studies. Also, the magnitude of the crisis suggests that the problems are fundamental and just not a transient phenomenon. What is striking is the contrast between this gloomy academic scene and the outside world. During my lecture tours in Europe, Australia and the United States, I found no lack of interest, especially among the youth. Only they are getting what they want from programs outside academic departments, in cultural centers like the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, temples, and short courses and seminars conducted by visiting lecturers (like this writer).

This means the demand is there, but academic departments are being bypassed. Even for learning Sanskrit, there are now innovative programs like those offered by Samskrita Bharati that teach in ten intensive yet lively sessions more than what students learn in a semester of dry lectures. The same is true of other topics related to India— history, yoga, philosophy and others. And this interest is by no means limited to persons of Indian origin. What has gone wrong with academic Indology, and can it be reversed?

To understand the problem today it is necessary to visit its peculiar origins. Modern Indology began with Sir William Jones’s observation in 1784 that Sanskrit and European languages were related. Jones was a useful linguist but his main job was to interpret Indian law and customs to his employers, the British East India Company. This dual role of Indologists as scholars as well as interpreters of India continued well into the twentieth century. Many Indologists, including such eminent figures as H.H. Wilson and F. Max Müller sought and enjoyed the patronage of the ruling powers.

Indologists’ role as interpreters of India ended with independence in 1947, but many Indologists, especially in the West failed to see the writing on the wall. They continued to get students from India, which seems to have lulled them into believing that it would be business as usual. But today, six decades later, Indian immigrants and persons of Indian origin occupy influential positions in business, industry and now the government in the United States and Britain. They are now part of the establishment in their adopted lands. No one in the West today looks to Indology departments for advice on matters relating to India when they can get it from their next door neighbor or an office colleague. In this era of globalization, India and Indians are not the exotic creatures they were once seen to be.

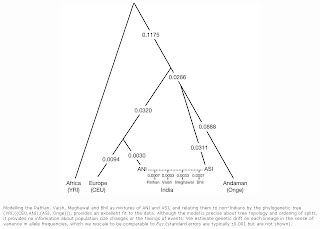

This means the Indologist’s position as interpreter of India to the West, and sometimes even to Indians, is gone for good. But this alone cannot explain why their Sanskrit and related programs are also folding. To understand this we need to look further and recognize that new scientific discoveries are impacting Indology in ways that could not be imagined even twenty years ago. This is nothing new. For more than a century, the foundation of Indology had been linguistics, particularly Sanskrit and Indo-European languages. While archaeological discoveries of the Harappan civilization forced Indologists to take this hard data also into their discipline, they continued to use their linguistic theories in interpreting new data. In effect, empirical data became subordinate to theory, the exact reverse of the scientific approach.

These often forced interpretations of hard data from archaeology and even literature were far from convincing and undermined the whole field including linguistics of which Sanskrit studies was seen as a part. The following examples highlight the mismatch between their theories and data. Scholars ignored obvious Vedic symbols like: svasti and the om sign found in Harappan archaeology; the clear match between descriptions of flora and fauna in the Vedic literature and their depictions in Harappan iconography; and also clear references to maritime activity and the oceans in the Vedic literature while their theories claimed that the Vedic people who composed the literature were from a land-locked region and totally ignorant of the ocean. Such glaring contradictions between their theories and empirical data could not but undermine the credibility of the whole field.

All this didn’t happen overnight: Harappan archaeology posed challenges to colonial Indological model of ancient India, built around the Aryan invasion model nearly a century ago. But the challenge was ignored because the political authority that supported Western Indologists and their theories did not disappear until 1950, while its academic influence lingered on for several more decades. It is only now, long after the disappearance of colonial rule that academic departments in the West are beginning to feel the heat.

Colonial Indology

Modern Indology may be said to have begun with Sir William Jones, a Calcutta judge in the service of the East India Company. One can almost date the birth of Indology to February 12, 1784, the day on which Jones observed:

The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of wonderful structure; more perfect than Greek, more copious than Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of the verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong, indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three without believing them to have sprung from some common source…

With this superficial, yet influential observation, Jones launched two fields of study in Western academics— philology (comparative linguistics) and Indo-European Studies including Indology. The ‘common source,’ variously called Indo-European, Proto Indo-European, Indo-Germanische and so forth has been the Holy Grail of philologists. The search for the common source has occupied philologists for the greater part of two hundred years, but the goal has remained elusive, more of which later.

Jones was a linguist with scholarly inclinations but his job was to interpret Indian law and customs to his employer— the British East India Company in its task of administering its growing Indian territories. In fact, this was what led to his study of Sanskrit and its classics. This dual role of Indologists as scholars as well as official interpreters of India to the ruling authorities continued well into the twentieth century. Many Indologists, including such highly regarded figures as H.H. Wilson and F. Max Müller enjoyed the support and sponsorship of the ruling powers. It was their means of livelihood and they had to ensure that their masters were kept happy.

Though Jones was the pioneer, the dominant figure of colonial Indology was Max Müller, an impoverished German who found fame and fortune in England. While a scholar of great if undisciplined imagination, his lasting legacy has been the confusion he created by conflating race with language. He created the mythical Aryans that Indologists have been fighting over ever since. Scientists repeatedly denounced it, but Indologists were, and some still are, loathe to let go of it. As far back as 1939, Sir Julian Huxley, one of the great biologists of the twentieth century summed up the situation from a scientific point of view:

In 1848 the young German scholar Friedrich Max Müller (1823 – 1900) settled in Oxford where he remained for the rest of his life… About 1853 he introduced into English usage the unlucky term Aryan, as applied to a large group of languages. His use of this Sanskrit word contains in itself two assumptions— one linguistic,… the other geographical. Of these the first is now known to be erroneous and the second now regarded as probably erroneous. [Sic: Now known to be definitely wrong.] Nevertheless, around each of these two assumptions a whole library of literature has arisen.

Moreover, Max Müller threw another apple of discord. He introduced a proposition that is demonstrably false. He spoke not only of a definite Aryan language and its descendants, but also of a corresponding ‘Aryan race’. The idea was rapidly taken up both in Germany and in England…

In England and America the phrase ‘Aryan race’ has quite ceased to be used by writers with scientific knowledge, though it appears occasionally in political and propagandist literature… In Germany, the idea of the ‘Aryan race’ received no more scientific support than in England. Nevertheless, it found able and very persistent literary advocates who made it appear very flattering to local vanity. It therefore steadily spread, fostered by special conditions. (Emphasis added.)

These ‘special conditions’ were the rise of Nazism in Germany and British imperial interests in India. Its perversion in Germany leading eventually to Nazi horrors is well known. The less known fact is how the British turned it into a political and propaganda tool to make Indians accept British rule. A recent BBC report acknowledged as much (October 6, 2005):

It [Aryan invasion theory] gave a historical precedent to justify the role and status of the British Raj, who could argue that they were transforming India for the better in the same way that the Aryans had done thousands of years earlier.

That is to say, the British presented themselves as ‘new and improved Aryans’ that were in India only to complete the work left undone by their ancestors in the hoary past. This is how the British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin put it in the House of Commons in 1929:

Now, after ages, …the two branches of the great Aryan ancestry have again been brought together by Providence… By establishing British rule in India, God said to the British, “I have brought you and the Indians together after a long separation, …it is your duty to raise them to their own level as quickly as possible …brothers as you are…”

Baldwin was only borrowing a page from the Jesuit missionary Robert de Nobili (1577 - 1656) who presented Christianity as a purer form of the Vedic religion to attract Hindu converts. Now, 300 years later, Baldwin and the British were telling Indians: “We are both Aryans but you have fallen from your high state, and we, the British are here to lift you from your fallen condition.” It is surprising that few historians seem to have noticed the obvious similarity.

In the circumstances it is hardly surprising that many of the ‘scholars’ of Indology should have had missionary links. In fact, one Colonel Boden even endowed a Sanskrit professorship at Oxford to facilitate the conversion of the natives to Christianity. (H.H. Wilson was the first Boden Professor followed by Monier Williams. Max Müller who coveted the position never got it. He remained bitter about it to the end of his life.)

It is widely held that Max Müller turned his back on his race theories when he began to insist that Aryan refers to language and never a race. The basis for this belief is the following famous statement he made in 1888.

I have declared again and again that if I say Aryan, I mean neither blood nor bones, nor skull nor hair; I mean simply those who speak the Aryan language. … To me an ethnologist who speaks of Aryan blood, Aryan race, Aryan eyes and hair is as great a sinner as a linguist who speaks of a dolichocephalic dictionary or a brachycephalic grammar.

What lay behind this extraordinary vehemence from a man noted for his mild language? Was there something behind this echo of the Shakespearean “Methinks the lady doth protest too much”?

Huxley attributes Max Müller’s change of heart to the advice of his scientist friends. This is unlikely. To begin with, the science needed to refute his racial ideas did not exist at the time. Moreover, Max Müller didn’t know enough science to understand it even if it were explained it to him. The reasons for his flip flop, as always with him, were political followed by concern for his position in England, not necessarily in that order.

A closer examination of the record shows that Max Müller made the switch from race to language not in 1888 but in 1871. That incidentally was the year of German unification following Prussian victory in the Franco-Prussian War. Thereby hangs a tale.1

For more than twenty years, from 1848 to 1871, Max Müller had been a staunch German nationalist arguing for German unification. He was fond of publicity and made no secret of his political leanings in numerous letters and articles in British and European publications. German nationalists of course had embraced the notion of the Aryan nation and looked to scholars like Max Müller to provide intellectual justification. He was more than willing to cooperate.

Things changed almost overnight when Prussia defeated France in the Franco-Prussian War leading to German unification under the Prussian banner. From a fragmented landscape of petty principalities, Germany became the largest and most powerful country in Europe and Britain’s strongest adversary. There was near hysteria in British Indian circles that Sanskrit studies had brought about German unification as the mighty ‘Aryan Nation’. Sir Henry Maine, a member of the Viceroy’s Council went so far as so claim “A nation has been born out of Sanskrit!”

The implication was clear, what happened in Germany could happen also in India, leading to a repeat of 1857 but with possibly a different result. All this was hysteria of the moment, but Max Müller the Aryan Sage, and outspoken German Nationalist faced a more immediate problem: how to save his position at Oxford? He had to shed his political baggage associated with the Aryan race and the Aryan Nation to escape any unfriendly scrutiny by his British patrons.

He could of course have gone along quietly but Max Müller being Max Müller, he had to strike a dramatic pose and display his new avatar as a staunch opponent of Aryan theories. In any event he was too much of a celebrity to escape unnoticed, any more than Michael Witzel or Romila Thapar could in our own time. So, within months of the proclamation of the German Empire (18 January 1871) Friedrich Max Müller marched into a university in Strasburg in German occupied France (Alsace) and dramatically denounced what he claimed were distortions of his old theories. He insisted that they were about languages and race had nothing to do with them.

He may have rejected his errors, but his followers, including many quacks and crackpots kept invoking his name in support of their own ideas. The climate in Oxford turned unfriendly and many former friends began to view him with suspicion. In fact, the situation became so bad that in 1875, he seriously contemplated resigning his position at Oxford and returning to Germany. Though there have been claims that this was because he was upset over the award of an honorary degree to his rival Monier-Williams, the more probable explanation is the discomfort resulting from his German nationalist past in the context of the changed situation following German unification.

The specter of Max Müller looms large over the colonial period of Indology though he is unknown in Germany today and all but forgotten in England. In fact his father Wilhem Müller, a very minor German poet is better known: a few of his poems were set to music by the great composer Franz Schubert. In his own time, Germans despised him for having turned his back on the ‘Aryan race’ to please his British masters. Indians though still revere him though no one today takes his theories seriously. One can get and idea of how he was seen by his contemporaries and immediate successors from the entry in the eleventh edition (1911) of the Encyclopædia Britannica:

Though undoubtedly a great scholar, Max Müller did not so much represent scholarship pure and simple as her hybrid types— the scholar-author and the scholar-courtier. In the former capacity, though manifesting little of the originality of genius, he rendered vast service by popularizing high truths among high minds [and among the highly placed]. …There were drawbacks in both respects: the author was too prone to build on insecure foundations, and the man of the world incurred censure for failings which may perhaps be best indicated by the remark that he seemed too much of a diplomatist.

His contemporaries were less charitable. They charged that Max Müller had an eye “only for crowned heads.” His acquaintances included a large number of princes and potentates—with little claim to scholarship—with a maharaja or two thrown in. He was fortunate that the British monarchy was of German origin (Hanoverian) and Queen Victoria’s husband a German prince (Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha). It was these more than fellow scholars that he cultivated. It proved valuable for his career, if not scholarship, for he had little difficulty in getting sponsors for his ambitious projects. He lived and died a rich man, drawing from his rival William Dwight Whitney the following envious if tasteless remark: 2

He has had his reward. No man was before ever so lavishly paid, in money and in fame, even for the most unexceptional performance of such a task. For personal gratitude in addition, there is not the slightest call. If Müller had never put his hand to the Veda, his fellow-students would have had the material they needed perhaps ten years earlier, and Vedic studies would be at the present moment proportionately advanced. …The original honorarium, of about £500 a volume, is well-nigh or quite unprecedented in the history of purely scholarly enterprises; and the grounds on which the final additional gift of £2000 was bestowed have never been made public.

Max Müller’s career illustrates how Indology and Sanskrit studies in the West have always been associated with politics at all levels. He was by no means the only ‘diplomatist’ scholar gracing colonial Indology, only the most successful. It is remarkable that though his contributions are all but forgotten, his political legacy endures. His successors in Europe and America have been reduced to play politics at a much lower level, but in India, his theories have had unexpected fallout in the rise of Dravidian politics. It is entirely proper that while his scholarly works (save for translations) have been consigned to the dustbin of history, his legacy endures in politics. This may prove to be true of Indology as a whole as an academic discipline.

Post colonial scene: passing of the Aryan gods

The post colonial era may conveniently be dated to 1950. In 1947 India became free and the great Aryan ‘Thousand Year Reich’ lay in ashes. In Europe at least the word Aryan came to acquire an infamy comparable to the word Jihadi today. Europeans, Germans in particular, were anxious to dissociate themselves from it. But there remained a residue of pre-war Indology (and associated race theories) that in various guises succeeded in establishing itself in academic centers mainly in the United States. Its most visible spokesman in recent times has been one Michael Witzel, a German expatriate like Max Müller, teaching in the Sanskrit Department at Harvard University in the United States. In an extraordinary replay of Max Müller’s political flip-flops Witzel too is better known for his political and propaganda activities than any scholarly contributions. Witzel’s recent campaigns, from attempts to introduce Aryan theories in California schools to his ill-fated tour of India where his scholarly deficiencies were exposed in public highlight the dependence of Indology on politics.

While the field of Indo-European Studies has been struggling to survive on the fringes of academia, lately it has become the subject critical analysis by scholars in Europe and America. Unlike Indians who treat the field and its practitioners with a degree of respect, European scholars have not hesitated to call a spade a spade, treating it as a case of pathological scholarship with racist links to Nazi ideology. This may be attributed to the fact that Europeans have seen and experienced its horrors while Indians have only read about it.

In a remarkable article, “Aryan Mythology As Science And Ideology” (Journal of the American Academy of Religion1999; 67: 327-354) the Swedish scholar Stefan Arvidsson raises the question: “Today it is disputed whether or not the downfall of the Third Reich brought about a sobering among scholars working with 'Aryan' religions.” We may rephrase the question: “Did the end of the Nazi regime put an end to race based theories in academia?”

An examination of several humanities departments in the West suggests otherwise: following the end of Nazism, academic racism may have undergone a mutation but did not entirely disappear. Ideas central to the Aryan myth resurfaced in various guises under labels like Indology and Indo-European Studies. This is clear from recent political, social and academic episodes in places as far apart as Harvard University and the California State Board of Education. But there was an interregnum of sorts before Aryan theories again raised their heads in West.

Two decades after the end of the Nazi regime, racism underwent another mutation as a result of the American Civil Rights Movement led by Dr. Martin Luther King. Thanks to the Civil Rights Movement, Americans were made to feel guilty about their racist past and the indefensible treatment of African Americans. U.S. academia also changed accordingly and any discourse based on racial stereotyping became taboo. Soon this taboo came to be extended to Native Americans, Eskimos and other ethnic groups.

In this climate of seeming liberal enlightenment, one race theory continued to flourish as if nothing had changed. Theories based on the Aryan myth that formed the core of Nazi ideology continued in various guises, as previously noted, in Indology and Indo-European Studies. Though given a linguistic and sometimes a cultural veneer, these racially sourced ideas continue to enjoy academic respectability in such prestigious centers as Harvard and Chicago.

Being a European transplant, its historical trajectory was different from the one followed by American racism. Further, unlike the Civil Rights Movement, which had mass support, academic racism remained largely confined to academia. This allowed it to escape public scrutiny for several decades until it clashed with the growing Hindu presence in the United States. Indians, Hindus in particular saw Western Indology and Indo-European Studies as a perversion of their history and religion and a thinly disguised attempt to prejudice the American public, especially the youth, against India and Hinduism to serve their academic interests.

The fact that Americans of Indian origin are among the most educated group ensured that their objections could not be brushed away by ‘haughty dismissals’ as the late historian of science Abraham Seidenberg put it. Nonetheless, scholars tried to use academic prestige as a bludgeon in forestalling debate, by denouncing their adversaries as ignorant chauvinists and bigots unworthy of debate. But increasingly, hard evidence from archaeology, natural history and genetics made it impossible to ignore the objections of their opponents, many of whom (like this writer) were scientists. But in November 2005, there came a dramatic denouement, in, of all places, California schools. Academics suddenly found it necessary to leave their ivory towers and fight it out in the open, in full media glare— and under court scrutiny.

It is unnecessary to go into the details of the now discredited campaign by Michael Witzel and his associates trying to stop the removal of references to the Aryans and their invasion from California school books. What is remarkable is that a senior tenured professor at Harvard of German origin should concern himself with how Hinduism is taught to children in California. Witzel is a linguist, but he presumed to tell California schools how Hinduism should be taught to children. It turned out that Hinduism was only a cover, and his concern was saving the Aryan myth from being erased from books.

Ever since he moved to Harvard from Germany, Witzel has seen the fortunes of his department and his field, gradually sink into irrelevance. Problems at Harvard are part of a wider problem in Western academia in the field of Indo-European Studies. As previously noted, several ‘Indology’ departments—as they are sometimes called—are shutting down across Europe. One of the oldest and most prestigious, at Cambridge University in England, has just closed down. This was followed by the closure of the equally prestigious Berlin Institute of Indology founded way back in 1821. Positions like the one Witzel holds (Wales Professor of Sanskrit) were created during the colonial era to serve as interpreters of India. They have lost their relevance and are disappearing from academia. This was the real story, not teaching Hinduism to California children.

Witzel’s California misadventure appears to have been an attempt to somehow save his pet Aryan theories from oblivion by making it part of Indian history and civilization in the school curriculum. Otherwise, it is hard to see why a senior, tenured professor at Harvard should go to all this trouble, lobbying California school officials to have its Grade VI curriculum changed to reflect his views.

To follow this it is necessary to go beyond personalities and understand the importance of the Aryan myth to Indo-European Studies. The Aryan myth is a European creation. It has nothing to do with Hinduism. The campaign against Hinduism was a red herring to divert attention from the real agenda, which was and remains saving the Aryan myth. Collapse of the Aryan myth means the collapse of Indo-European studies. This is what Witzel and his colleagues are trying to avert. For them it is an existential struggle.

Americans and even Indians for the most part are unaware of the enormous influence of the Aryan myth on European history and imagination. Central to Indo-European Studies is the belief—it is no more than a belief—that Indian civilization was created by an invading race of ‘Aryans’ from an original homeland somewhere in Eurasia or Europe. This is the Aryan invasion theory dear to Witzel and his European colleagues, and essential for their survival. According to this theory there was no civilization in India before the Aryan invaders brought it— a view increasingly in conflict with hard evidence from archaeology and natural history.

In this academic and political conundrum it is important not to lose sight of the fact that the Aryan myth is a modern European creation. It has little to do with ancient India. The word Arya appears for the first time in the Rig Veda, India’s oldest text. Its meaning is obscure but it seems to refer to members of a settled agricultural community. It later became an honorific and a form of address, something like ‘Gentleman’ in English or ‘Monsieur’ in French. Also, it was nowhere as important in India as it came to be in Europe. In the whole the Rig Veda, in all of its ten books, the word Arya appears only about forty times. In contrast, Hitler’s Mein Kampf uses the term Arya and Aryan many times more. Hitler did not invent it. The idea of Aryans as a superior race was already in the air— in Europe, not India.3

It is interesting to contrast Witzel’s political campaigns against Max Müller’s. Where Max Müller hobnobbed with Indian and European aristocracy including princes and Maharajas, Witzel has had to content himself waiting on California schoolteachers and bureaucrats. These were his masters who held the keys to his career and reputation. It may be no more than a reflection of changed circumstances and the loss of power and prestige of the aristocracy but the contrasts are nonetheless striking.

No less striking is the contrast between their legacy and reputation. While we may look at Max Müller’s foibles and failures with amused tolerance and appreciate his monumental work in compiling the fifty-volume Sacred Books of the East, Witzel’s name is unlikely to command any respect much less affection. In addition to his support for the Aryan theories and the California campaign, Witzel is known for his association with the notorious Indo-Eurasian Research (IER), which has been accused of a hate campaign against the Hindus.

An article that appeared the New Delhi daily The Pioneer (December 25, 2005) began: “Boorish comments denigrating India, Hindus and Hinduism by a self-proclaimed ‘Indologist’ who is on the faculty of Harvard University has unleashed a fierce debate over the increasing political activism of ’scholars’ who teach at this prestigious American university. Prof Michael Witzel, Wales professor of Sanskrit at Harvard, is in the centre of the storm because he tried to prevent the removal of references to India, Hinduism and Sikhism in the curriculum followed by schools in California which parents of Indian origin found to be inadequate, inaccurate or just outright insensitive.”

The author of The Pioneer article (Kanchan Gupta) went on to observe: “Witzel declared Hindu-Americans to be "lost" or "abandoned", parroting anti-Semite slurs against Jewish people. Coincidence or symptom? Witzel's fantasies are ominously reminiscent of WWII German genocide. He says that 'Since they won't be returning to India, [Hindu immigrants to the USA] have begun building crematoria as well. … Witzel demeans the daughters of Indian-American parents, who take the trouble to learn their heritage through traditional art forms. In the worst of racist slander, Witzel claims that Indian classical music and dance reflect low moral standards.”

One cannot imagine any publication today, let alone in India, write in this vein about Max Müller, whatever one may feel about his politics and scholarship. Nor can one imagine Max Müller write in the style of Witzel about India or anyone else.

It must be recorded that Max Müller was emphatically not a racist. He was also a man of exemplary humility in dealing with fellow scholars. In a letter to the Nepalese scholar and Sanskrit poet Pandit Chavilal (undated but written probably just before 1900) Max Müller wrote:

I am surprised at your familiarity with Sanskrit. We [Europeans] have to read but never to write Sanskrit. To you it seems as easy as English or Latin to us… We can admire all the more because we cannot rival, and I certainly was filled with admiration when I read but a few pages of your Sundara Charita.

This reflects great credit on Max Müller as a scholar. One has to wonder if his present day counterparts are capable of such exemplary humility. Certainly none was in evidence during Michael Witzel’s recent disastrous lecture tour of India where he was severely embarrassed by schoolchildren and scholars alike, where he was shown to be completely at sea with basic rules of Sanskrit grammar. More than a hundred years ago, Max Müller declined invitations to visit India probably because he sensed that a similar fate awaited him. He chose discretion over bravado.

The decline from Max Müller to Witzel serves as a metaphor for the decline of Indology itself in our time.

State of Sanskrit studies in the West

In recent months there have been cries of ‘Sanskrit in danger of disappearing’ from Sanskrit professors and other Indologists in Western academia. This is certainly true in their own case, but their next claim that they need more funding (what else?) to reverse the decline must be taken with a large grain of salt. Sanskrit existed and flourished for thousands of years before Indology and Indologists came into existence, and will no doubt continue to exist without them. If Sanskrit ever faces extinction, it will be for reasons of social and political developments in India and not due to lack of funds for Indologists in the West. They can no more save Sanskrit than Indian scholars can save classical Greek.

We may now take a moment to assess the contribution of Western Sanskritists from an Indian perspective. For those who believe that Western scholarship has made a major contribution to Sanskrit, such people are not limited to the West, here is an objective measure to consider: Indians began studying English (and other European languages) about the same time that Europeans began their study of Sanskrit. Many Indians have attained distinction as writers in English. But there is not a single piece in Sanskrit—not even a shloka (verse)—by a Western Sanskritist that has found a place in any anthology. This was acknowledged by no less an authority than Max Müller in passage quoted at the end of the previous section.

These are not the people who can ‘save’ Sanskrit, even if it needs to be saved. Sanskrit is India’s responsibility just as Greek and Latin are Europe’s. Let them study Sanskrit just as Indians should study Greek, but it is too much to expect a few sanctuaries in the West protect and nurture a great and ancient tradition when they are having a hard time saving themselves.

The principal contribution of the West has been in bringing out editions of ancient works like the Rigveda and translations like Max Müller’s monumental fifty volume Sacred Books of the East. These too have their limitations.

Summary and conclusions

We may now conclude that that Western Indology is in steep decline and may well become extinct in a generation. The questions though go beyond Indology. Sanskrit is the foundation of Indo-European Studies. If Sanskrit departments close, what will take their place? Will these departments now teach Icelandic, Old Norse or reconstructed Proto Indo-European? Will they attract students? Can Indo-European Studies survive without Sanskrit? A more sensible course would be for Indian and Western scholars to collaborate and build an empirically based study of ancient Indian and European languages— free of dogma and free of politics.

A basic problem is that for reasons that have little to do with objective scholarship, Indologists have been trying to remove Sanskrit from the special space it occupies in the study of Indo-European languages and replace it something called Proto-Indo-European of PIE. This is like replacing Hebrew with a hypothetical Proto-Semitic language in Biblical Studies. This PIE has literally proven to be a pie in the sky and the whole field is now on the verge of collapse. The resulting vacuum has to be filled by a scholarship that is both sound and empirical, based on existing languages like Sanskrit, Greek and the like. Additionally, Indian scholars will have look more to the east and search for linguistic and other links to the countries and cultures of Indonesia, Cambodia, Vietnam and others that have historic ties to India of untold antiquity.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

This is explained in more detail in this writer’s The Politics of History and also in Vedic Aryans and the Origins of Civilization, Third Edition, by Navaratna Rajaram and David Frawley, both published by Voice of India, New Delhi. Some recent developments may be found in Sarasvati River and the Vedic Civilization by N.S. Rajaram, Aditya Prakashan, New Delhi. For the record the full name of Max Müller was Friedrich Maximillian Müller, but he is better known as Max Müller, the name used also by his descendants.

Max Müller’s aristocratic Indian friends included the Raja of Venkatagiri (who partly financed his edition of the Rigveda) as well as Dwarakanath Tagore, the grandfather of the Nobel laureate Rabindranath. When Max Müller was a struggling scholar in Paris, Tagore helped him with Sanskrit as well as financially. He knew also British and European nobility having met Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. In his early years his patrons included Dwarakanath Tagore and Baron Bunsen, the Prussian Ambassador to Britain. It is a tribute to Max Müller’s personality and liberal character that he could attract the friendship of such a wide range of people.

3. It should be noted that the Nazis appropriated their ideas and symbols from European mythology, not India. Hitler’s Aryans worshipped Apollo and Odin, not Vedic deities like Indra and Varuna. His Swastika was also the European ‘Hakenkreuz’ or hooked cross and not the Indian svasti symbol. It was seen in Germany for the first time when General von Luttwitz’s notorious Erhardt Brigade marched into Berlin from Lithuania in support of the abortive Kapp Putsch of 1920. The Erhardt Brigade was one of several freebooting private armies during the years following Germany’s defeat in World War I. They had the covert support of the Wehrmacht (Army headquarters).